This blog features an interview of Alpine Security’s CEO, Christian Espinosa, on medical device security by Caroline Cornell, originally posted at classaction.com.

Could you provide an overview of the cybersecurity threats the medical field faces? How big is this problem?

Medical devices have largely been neglected from a cybersecurity perspective. Many of these devices run legacy operating systems, are full of vulnerabilities, and were not intended to be connected to hospital networks. For ease of management, data access, updates, etc., many medical devices are now connected to hospital networks, which have connections to the Internet.

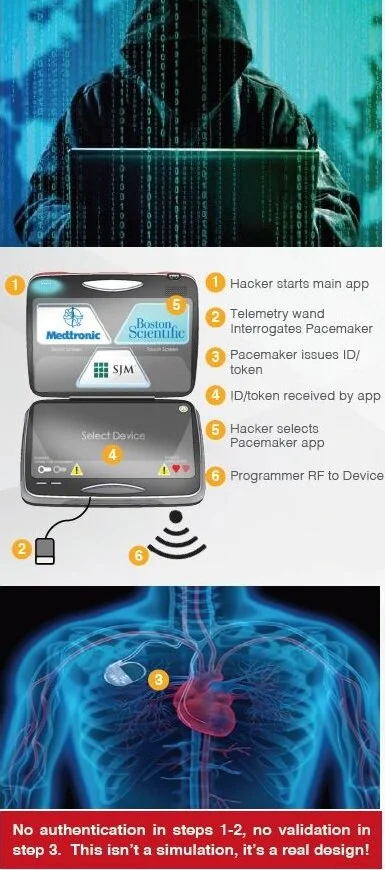

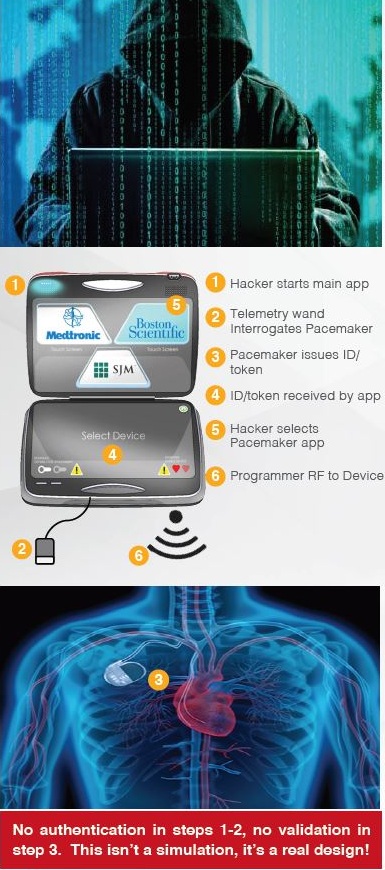

Hospital networks are inherently unsecure; any threats to a hospital network are transferred to connected medical devices. Threats to implantable devices are primarily due to unsecure wireless communications. Implantables were designed to be easy to monitor and update via wireless technology. It is too risky to perform heart surgery every time a pacemaker or implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) needs to be updated, for example.

The threats to medical devices are a big problem with severe and potentially lethal consequences.

As a white hat hacker, what’s your process for identifying security vulnerabilities? Do you try to hack everything and anything, or do you gravitate towards particular types of devices or networks?

Our process depends on the scope of the engagement. If we are asked to assess a medical device, we typically have several main phases—1) we perform a discovery to learn more about the device; 2) we define a security boundary for the device; 3) we perform a risk assessment of the device; 4) we identify all possible entry points in the system/device; 5) we develop attack trees and assess all entry points into the system using penetration testing and other techniques; 6) based on the results of 1-5, we determine a mitigation strategy; 7) we generate the report.

As for hacking everything and anything, the process I just mentioned applies a risk-based approach to our assessment. We focus on the big-ticket items first with the highest risk to patient safety, emphasizing how the device could be misused and the effect of attacks on data confidentiality, integrity, and availability. We work with manufacturers and providers to fix the most critical items first, then work down a prioritized list, based on the risk. We also run validation tests to ensure remediation steps worked.

How receptive are companies when you do identify a vulnerability? Do they usually address the issue?

Some are more receptive than others. Sometimes we are met with resistance, such as “there’s no way someone would think of doing that.” Most often though, our findings are well-received.

Unfortunately, company bureaucracy, cost, timelines, and other factors present obstacles to fixing devices under development or devices deployed in the field. It is very costly for medical device manufacturers to fix devices that are deployed across the world, or ones that are in the middle of development.

What do you think makes medical devices and hospital networks so appealing to hackers?

A couple reasons. One is that PHI (protected health information) is more valuable than other types of information. Patient records sell for more than other types of stolen sensitive data on the black market.

Another reason is the physical effects that can be caused by hacking medical devices. Normally, if you steal credit card data from a web application, you may inconvenience someone—that’s an indirect effect to the person. If you can hack into a medical device though, you can directly affect a person’s physical state and well-being.

What is the one type of security vulnerability that keeps you up at night?

There’s not one that keeps me up at night. I’ve come to terms with the fact that it’s just a matter of time before something catastrophic happens. There’s already been many warning signs, yet there is a head-in-the-sand mindset still. Almost like “if we pretend it’s not there, the threat doesn’t exist.”

If I had to pick one threat that would keep me up at night though, it is the threat of weaponized medical nanotechnology, a form of biomedical hacking.

Nanotechnology, or “nanotech,” are basically extremely small computers, smaller than a pinhead. Nanobots can be used in the human body for items such as targeting cancer cells to destroy them by delivering chemotherapy to only cancer cells.

These nanobots can also be used to deliver lethal toxins or carry out specific missions in the human body, such as making your arms temporarily unmovable, or similar. The scary thing is they can be introduced to the human body very easily. You could breathe them in and not even know.

Do you think the FDA is doing enough to prevent and respond to cyberattacks?

I think the challenge is identifying who is ultimately responsible for medical device security—the device manufacturer, the user, the hospital, clinic, the Department of Homeland Security, the FDA, the doctor, patient, etc.?

The FDA has basically issued premarket and postmarket guidance for medical devices and passed the responsibility to healthcare delivery organizations (HDOs). According to the FDA, “HDOs are responsible for implementing devices on their networks and may need to patch or change devices and/or supporting infrastructure to reduce security risks. Recognizing that changes require risk assessment, the FDA recommends working closely with medical device manufacturers to communicate changes that are necessary.”

We recently spoke with a medical professional who told us that “doctors don’t become doctors to protect data.” What role does the average doctor play in maintaining secure medical devices and networks?

I agree with this statement. Doctors have enough to worry about. They should be given a list of “approved medical devices” that they can use and recommend. These devices should be thoroughly vetted for cybersecurity vulnerabilities. Penetration testing and other methods should be used.

The challenge becomes where does this “approved list of medical devices” come from? Who has the approval authority? This is not a simple problem to solve, because medical devices are complex systems with many vulnerabilities, both known and unknown. What is approved today, could be recalled tomorrow. This should not be the responsibility of the doctor.